Weather Report: On Beauty

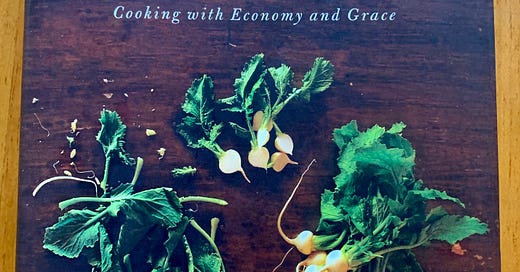

Post #10: "An Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace", by Tamar Adler

If you have a copy of my book, Weather Report: A 90-day journal for reflection and well-being, with the aid of the Beaufort Wind Scale, you might have noticed two things; that you are daily invited to write or draw, 'one thing you found beautiful today', and a list of reading resources at the back. These are not unconnected.

This is a year-long project to write weekly, choosing one of the books from that list with a few wildcards too. I want to go deeper into the subject of beauty and, together with you who join me here, to deepen my own understanding of why it is important. Some of the books on the list are very recent; others are long-standing companions that I return to over and over. To me these are the kind of books that, having read them, I can gain solace simply from having them on my shelves.

~~

Tamar Adler’s book, An Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace, is a hymn to food, to the art of cooking, sharing and generally being generous and joyful around this daily task. Unusually for a cookbook there are no glossy photos here, no carefully staged plates of artfully styled and synthetically coloured meals. Instead we are treated in glorious prose to the possibilities in a myriad of ordinary, dare I say humble, ingredients.

On Sunday evening last, as I was noodling this post around in my head and jotting down notes, I sliced a leek into finger sized lengths and added it to a nonstick pan with a little olive oil on a low heat to sauté. As it started to wilt and soften I added a splash of milk, then took an orange and grated a little of the rind into the leeks. Next I cut the orange in half and squeezed some juice into the pan, stirring everything together. We enjoyed it with some chicken left over from the previous day and a couple of boiled potatoes. I have no idea where I first came across the idea to add the rind and juice of an orange to some leeks but a bit like Adler’s book, no photograph could capture the flavour or the aroma that hung around the kitchen for hours afterwards and which gave me such a feeling of warmth and pleasure everytime I passed through. It felt to me like the spirit of Adler’s book, especially the subtitle, ‘with economy and grace.’

“[This book] doesn’t contain “perfect” or “professional” ways to do anything, because we don’t need to be professionals to cook well, any more than we need to be doctors to treat bruises and scrapes: we don’t need to shop like chefs or cook like chefs; we need to shop and cook like people learning to cook, like what we are — people who are hungry.” (p. 2)

With intriguing chapter titles, such as ‘How to Paint without Brushes’; ‘How to Live Well’; ‘How to Have your Day’, Adler entices us to re-consider how we relate to food, how to be playful as we cook, how we might elevate the ordinary.

In the chapter titled, ‘How to Light a Room’, I wonder if you would guess the subject from the title? The chapter opens with this, “Little flourishes, like parsley, make food seem cared for. They are as practical as lighting candles to change the atmosphere of a room.” (p. 69)

Then continues…

“… roughly chop a big handful of parsley. It’s nice to have not just the impression of a leaf, but the experience of it when you eat one… Once parsley has been quickly chopped, throw a generous handful directly over your rice or potatoes or pasta, and watch the meal begin to prickle with feeling.” (p.70)

Just imagine the effect of a meal prickling with feeling. This is a book that is more about strategies, about mindset, about creativity and possibilities than it is about recipes or hard and fast rules: ‘Meals’ ingredients must be allowed to topple into one another like dominos… This continuity is the heart and soul of cooking.’ (p. 3) But there are also recipes, lots of them, scattered through the chapters.

There is more to eating food, real food, than simply counting calories or balancing macronutrients — and of course Adler doesn’t mention either. Here it is a means of building relationships, with food, with others and she notes that, “it’s pleasurable to spoon a potato onto a fellow diner’s plate. It binds you to her, for the duration of the dinner at least, in a way that makes conversation easy and the atmosphere good… Only remember what is plainly and always true: the act of serving fulfils itself. It doesn’t matter what you serve.” (p. 219 / 220)

The entire approach of this book, one that results in a kind of subtle seduction, is captured in the epigraph to the chapter titled, ‘How to Build a Ship’, from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (author of The Little Prince, see post #5):

“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood, and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

“I will only read a cookbook if it is one in which the poetry of food comes alive on the page”, writes Adler on p. 143. This is definitely one such book. A beauty.

How beautiful is this! Thank you Margaret.

Your prose compliments Tamar's so well. Now I'm going to have to get this book. A cook book without photos. How rare. Yet I can smell the food that I am visualizing. Just as the whiff of your orange rind hits my nostrils. Thanks Margaret.