If you have a copy of my book, Weather Report: A 90-day journal for reflection and well-being, with the aid of the Beaufort Wind Scale, you might have noticed two things; that you are daily invited to write or draw, 'one thing you found beautiful today', and a list of reading resources at the back. These are not unconnected.

This is a year-long project to write weekly, choosing one of the books from that list with a few wildcards too. I want to go deeper into the subject of beauty and, together with you who join me here, to deepen my own understanding of why it is important. Some of the books on the list are very recent; others are long-standing companions that I return to over and over. To me these are the kind of books that, having read them, I can gain solace simply from having them on my shelves.

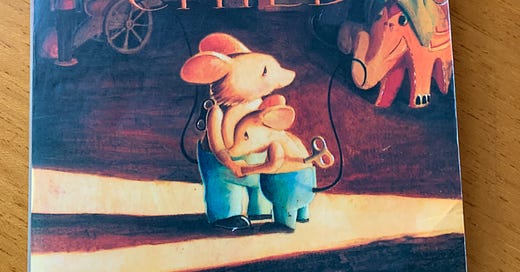

This week’s post is on Russell Hoban’s novel, The Mouse and His Child. Those who are paying attention will see that this little gem is not on the Resource List at the back of Weather Report, but is one of my promised ‘wildcards’.

Some years ago I was teaching on a BA module titled, ‘Literature of Family’, and after a little deliberation, and realising that all literature uses family as material in one way or another, I opted to use Hoban’s novel as my text.

The mouse and his child are clockwork toys who we meet in the toyshop in the opening pages as it is coming up to Christmas, poignantly through the eyes of a tramp who peers through the window but cannot gain access.

In good toy storytelling tradition, at the stroke of midnight, in the darkened and closed shop, all the toys come to life and can converse.

“Where are we?” the mouse child asked his father. His voice was tiny in the stillness of the night.

“I don’t know,” the father answered.

“What are we, Papa?”

“I don’t know. We must wait and see.” (Hoban, p.4)

And thus begins the quest to discover the answers to these big questions, and many others, and the profound discoveries that are made along the way.

Already the child mouse has an inchoate longing, knows he is missing something vital. “Are you my mama?” asked the child [of the plush elephant]. He had no idea what a mama might be, but he knew at once that he needed one badly. (Hoban, p. 7) They are of course soon cast out of the perfect but static world of the toyshop, first bought as toys for a family, then thrown out after being damaged by the family cat. Again, the tramp comes upon them, broken, and does some rudimentary repairs. They can no longer dance but can walk, the child backwards.

“Their patent leather shoes had been lost in the dust-bin; their blue velveteen trousers hung wrinkled and awry; their fur had come unglued in several places, but the mouse and his child were whole again.” (Hoban, p. 11)

He then instructs them to “Be tramps” and walks away.

They soon meet the menacing arch-manipulator Manny Rat, the fortune-telling Frog who is unsettled by what he sees in their future, plus a host of diverse creatures who play important roles in the journey of the mouse and his child. The latter continually aches for relationships, “Be my uncle… be my Uncle Frog” he asks the Frog (p. 31). All he wants is to ‘have a family and to be cosy’.

They encounter shrews at war over territory and the mouse child asks, “What’s a territory?”

“A territory is your place,” said the drummer boy. “It’s where everything smells right. It’s where you know the runways and the hideouts, night or day… you feel all safe and strong there. It’s the place where when you fight, you win.”

“That’s your territory,” said the fifer. “Somebody else’s territory is something else again. That’s where you feel all sick and scared and want to run away, and that’s where the other side mostly wins.”

The father walked in silence as a wave of shame swept over him. What chance has anybody got without a territory! he repeated to himself and knew the little shrew was right. What chance had they indeed! He saw now that for him and for his son the whole wide world was someone else’s territory, on which he could not even walk without someone to wind him up. Frog wound him now as they marched, and the father felt the key turn in his back as a knife turns in a wound. (Hoban, p. 40)

On they travel, encounter (and save) the Beckettian Caws of Art, the play is masterfully absurd, with its cast of crows:

“A large crow came walking out of the pines and cocked his head to listen. A tall, well-set-up bird, he wore his great black, glossy wings in the manner of a cloak thrown carelessly over his shoulder, and he had what his wife and fellow actors admiringly described as ‘presence’: wherever he was, he simply seemed to be there more intensely than any other bird.” (Hoban, p. 49)

The quest of the mouse and his child is for a home, for security (their territory) and to be self-winding. But in the beautiful and powerful ending, as the motley gathering somehow manage to create a home together, Frog realises that, ‘I don’t suppose anyone ever is completely self-winding. That’s what friends are for’ as he reached for the father’s key, to wind him up again.

I love this Margaret. Thank you for sharing with me and I want to buy the book now as well. :)

"... take action to build a world that supports and values diversity in all its richness? Could we?" We CAN! Thank you for this inspiration, Margaret!!