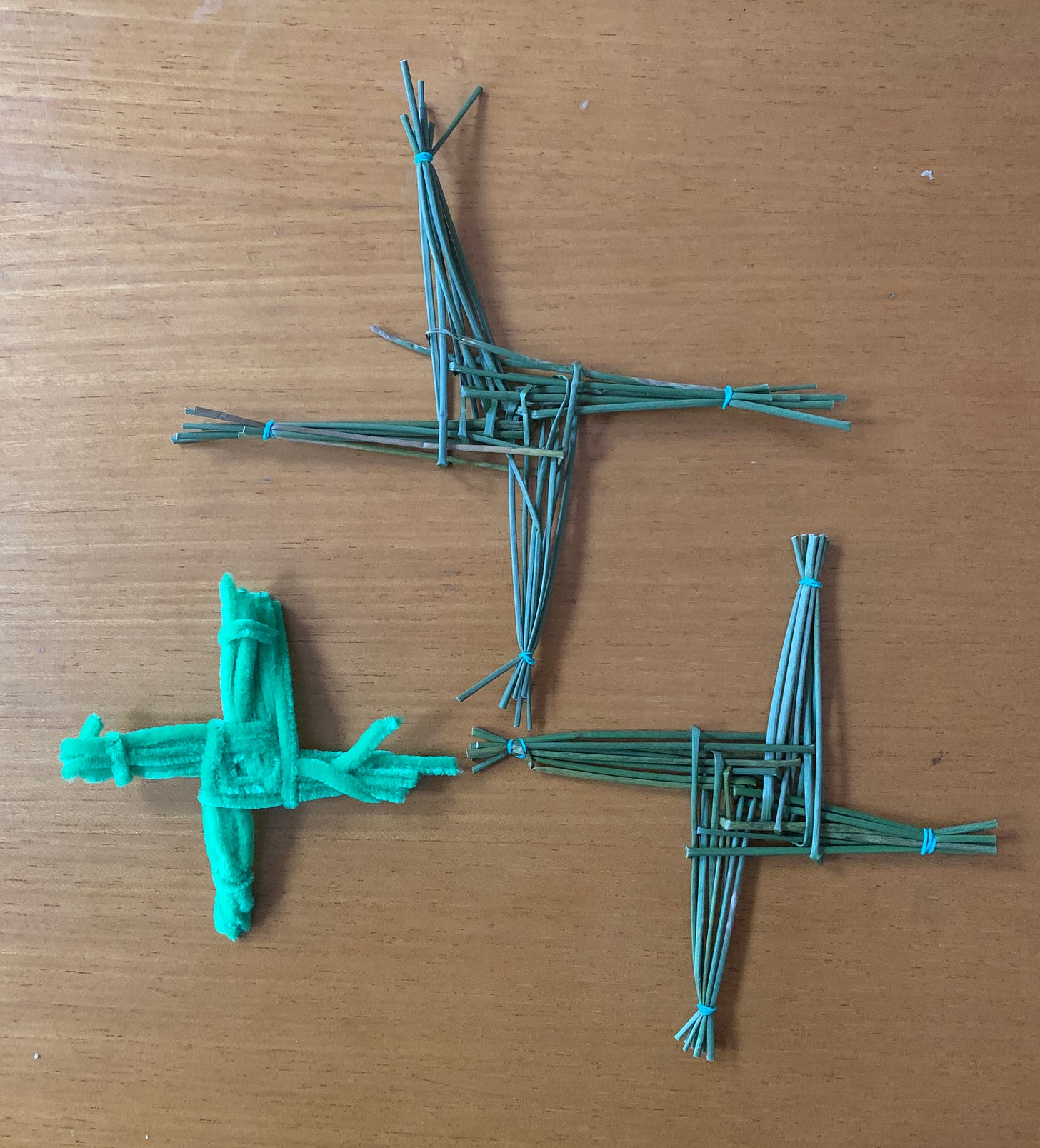

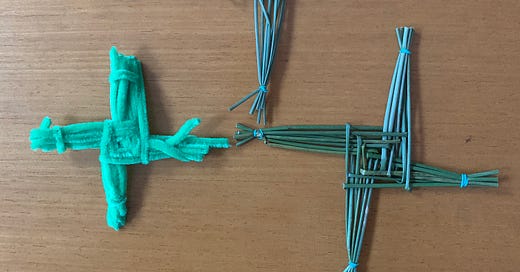

Today is the first of February and the days are visibly lengthening here, crocuses are appearing over ground, offering us promise and simple beauty. We are at Imbolc, moving towards the spring equinox. It is also of course the feast day of St. Bridget, one of the patron saints of Ireland in the Christian tradition and who may also have been a goddess. I spent a very enjoyable couple of hours upstairs in the Tudor Artisan Hub last Saturday morning learning, from an actual Druid, how to make a St. Bridget’s cross with traditional reeds. While my fingers struggled to control the reeds, which seemed to have a life of their own, the conversation ranged from the legends associated with Bridget to the sport of axe-throwing. That’s the delight of being together in-person and working with our hands. Conversations can roam wide and wild!

To mark this significant day I have included two pieces below, one for my late mother whose name was Bridget1, and the second includes another Bridget, this time Bridget Cleary. It’s a strange fact for me that my mother’s father, my grandfather, is buried beside the latter Bridget.

1. BRAT BRÍD or Bridget’s Cloak

“Something happens when your mother dies. Something, many things, unravel. Today I picked the card, The Spindle of Loss. It has snakes—two of them, wrapped around the spindle—their heads arched, tongues extended, poised for a victim.

I was aged five and my mother made dresses from polka dot cotton, summer dresses, one for me and one for her. She moved the fabric along under the needle of the singing machine as it stepped its way stitch by stitch along the seams. Bigger, smaller, we matched perfectly.

She was Bridget and she died in February, the month of Bridget or in the Celtic calendar, Imbolc, one of the four points of transition in the year. The saint named Bridget was also a goddess and she had special powers with cloth. When she gained the promise of land for her monastery from her bishop, it would be just enough to match the area of her cloak2. But Bridget had powers to draw on that were more than a match for the bishop. She agreed, we can imagine how that pleased him, and then trusted her powers that she would be given what was needed. The legend tells us that her cloak extended to cover a great area of Co. Kildare.

In a similar way, those dresses of polka dot cotton that made us a matching pair for that summer under the apple trees, have extended themselves in time and memory and those spitting snakes will gain no power of poison over them.”

2. Marked and unmarked (extract)

“We began our search in the obviously newer part of Cloneen graveyard with its shiny marble headstones in regular rows. Some had the surname I was looking for, Maher or Meagher, it’s not uncommon around here, but I come from poor stock and I knew my grandfather wouldn’t have had a fine marble headstone.

We stepped across the stile into the older more elevated part of the graveyard, with its crumbling ruin of some early church, roofless, open to the sky. Rooks flew among the trees in the next field and caw cawed their news to each other. Here, ancient headstones tottered at precarious angles, slowly but inevitably losing their initial thrust towards the sky. The wet grass began to seep through my shoes as I walked around, pausing here and there to attempt to decipher some script, and my feet became cold. We could see a couple of men working at some farm machinery beside a barn in the near distance but they showed no interest in our activities.

Bridget Cleary is also interred in this graveyard and I had heard that her grave was beside my grandfather’s. In the year 1895 Bridget, a young childless woman who earned her living as a seamstress, had been burned to death in her home by her husband Michael and some of her relatives, suspected by them, it was reported at the time, of being a changeling. She was not her real self, they claimed, but an inferior replacement left by the malevolent underworld. The ensuing trial was a cause célebre, with headlines such as the New York Times’ ‘barbarous episode near Fethard’ and from The Manchester Guardian, ‘Revolting Affair in Ireland: A Woman Burned to Death’.3

We continued to wander around this old graveyard, searching for Maher or Meagher, and Cleary. We had the place entirely to ourselves. As we were obviously searching and, on this elevated site, visible on all sides, I half-expected, even hoped, some curious local person would wander in to try to find out what we were after and maybe offer some local knowledge and guidance. Then Joe found the name Maher. A small stone marker upright in the grass by the boundary wall, the lettering almost indecipherable. We rubbed it with a fistful of damp grass and read: In loving memory of Ed Maher, Ballinard / His mother Ellen / Grandmother Norrie / May the Lord have mercy on their soles [sic]. Nothing else. No dates, no surname except his.

We stood in the wet grass as I rang my youngest brother and he confirmed that yes, that most likely was it. And he added that Grandad had made the headstone himself, that the misspelling of ‘souls / soles’ was his little joke. That he made it himself would explain why there was no date of death on it but what is not clear is why he chose to be buried here and not with his wife, Anastasia, who had predeceased him by some thirty years. She is instead buried in St. Mary’s, the cemetery over our back garden wall, with their son, my Uncle Johnny. Although I never knew her, this Anastasia—she died a couple of years before I was born—I carry her name in my middle initial, ‘A’. I puzzled over why my grandfather gave his address as Ballinard. He had lived all his mature adult life until his death in Carrick-on-Suir, many decades of married, family life with his two sons and his daughter, my mother. He left us no clues regarding dates of his own life or his mother or grandmother, no dates of birth or death. Nor their surnames.

Beside my grandfather’s grave there was no marker for Bridget Cleary, instead just bare rough grass and some low upright stones. I spoke to a writer friend in the locality who has an interest in local history. She cautioned that local people, more than a century later, still do not want to speak of this awful event. They still carry the shame, the stigma, both of the event and the reporting of it. Politically Ireland was struggling for Home Rule from Great Britain at the time and was, subsequent to the trial, cast as a people who were superstitious and incapable of governing themselves. That seems to explain why we had no curious locals come to see what two strangers were looking for, traipsing around among the ancient, toppling grave markers. But I don’t wish to come to a facile conclusion. Shame, and the resulting silence, can be easily explained but maybe not so easily understood. And further research I’ve carried out since indicates that Bridget Cleary’s grave does, in fact, remain unmarked4.

We found a grave that was marked, but which to me had maddeningly incomplete information. And we found that a grave was unmarked, in the expected sense, but yet present and freighted with tragedy and history.”

My post, ‘The View from Here is Love’, is a good companion read to this.

The legend of Bridget’s cloak

Angela Bourke’s book, The Burning of Bridget Cleary is a thorough and thoughtful account of this dreadful event.

Since originally writing this piece, I believe that very recently a small headstone has been place on Bridget Cleary’s grave.

"We found a grave that was marked but which to me had maddeningly incomplete information. And we found that a grave was unmarked, in the expected sense, but yet present and freighted with tragedy and history." What a lovely description of your search in the cemetery for stories of family and local lore. I love cemeteries too.

So lucky to have these ancestors and their stories so close, Margaret. Here in Melbourne, ancestors have such silenced histories. The Earth Carrie’s these stories but so often they do not speak.