Weather Report: On Beauty

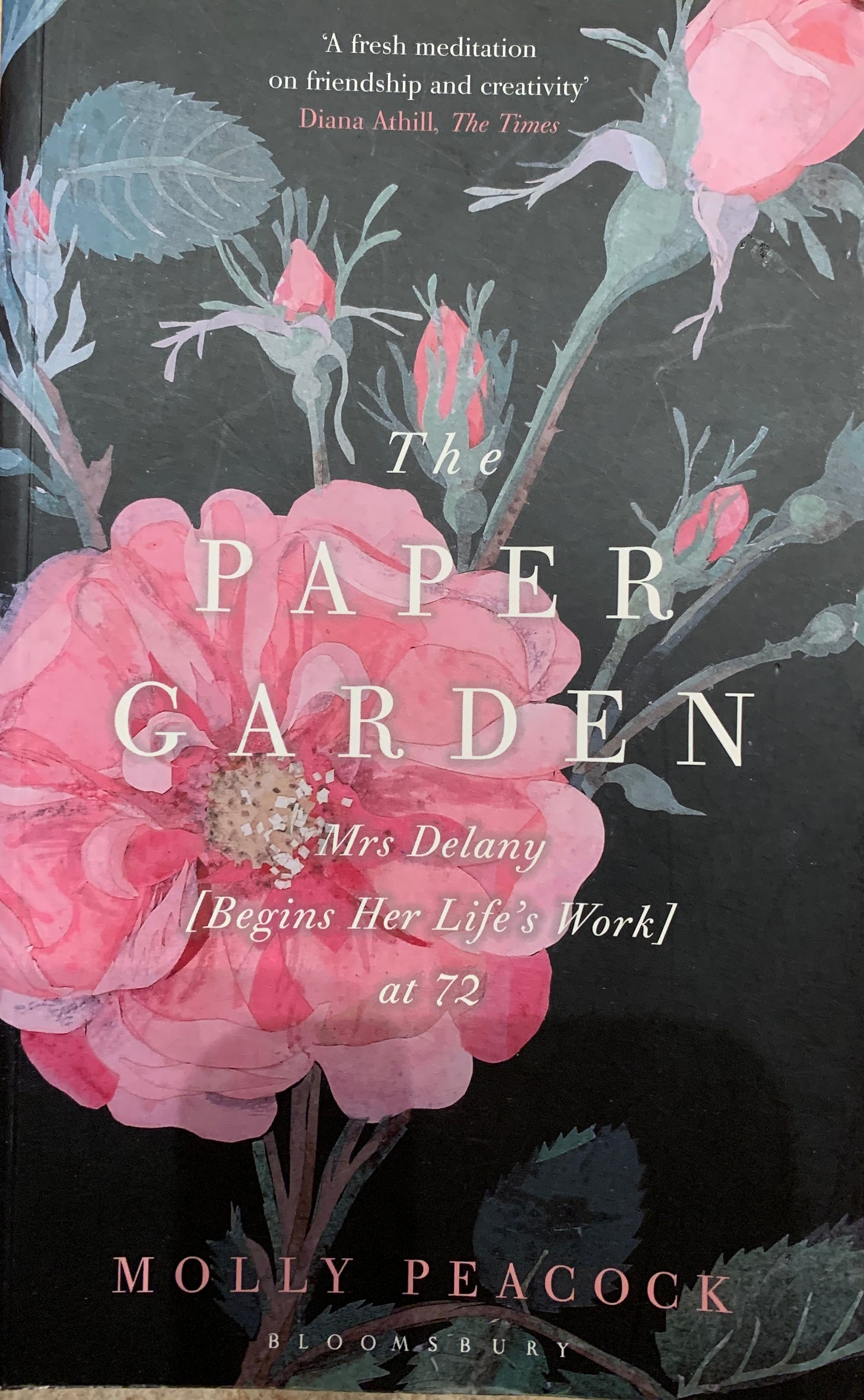

Post #7: "The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany [Begins Her Life's Work] at 72", by Molly Peacock

If you have a copy of my book, Weather Report: A 90-day journal for reflection and well-being, with the aid of the Beaufort Wind Scale, you might have noticed two things; that you are daily invited to write or draw, 'one thing you found beautiful today', and a list of reading resources at the back. These are not unconnected.

This is a project to write regularly on one of the books from that list with a few wildcards too. I want to go deeper into the subject of beauty and, together with you who join me here, to deepen my own understanding of why it is important. Some of the books on the list are very recent; others are long-standing companions that I return to over and over. To me these are the kind of books that, having read them, I can gain solace simply from having them on my shelves.

~~

Here I focus on the intriguingly titled, The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany [Begins Her Life's Work] at 72, by Canadian writer Molly Peacock. I see from the inside cover that I have my copy since May 2012, over a decade. This is most definitely one of those that is a long-standing companion of mine. Molly Peacock has written an engrossing recounting of the fascinating life of the eponymous Mrs. Delany, an 18th century woman, braided through with reflections from Peacock’s own life as a 21st century woman, mirroring her studying of Delany’s life with the latter’s close observations of flowers.

“She wasn’t an expert in anything except observing. And then she did something no one had ever done before.” (Peacock, p. 33)

Born Mary Granville in 1700, Mrs. Delany survived a marriage at age 17 to a drunken sixty-year old squire, flirted with Jonathan Swift, attended one of the first performances of Handel’s Messiah, saw the rise of coffee houses in England and much more.

At the age of 43 she finally married for love one Dean Patrick Delany, a Protestant Irish clergyman and friend of Jonathan Swift.

In 1772, four years after Patrick Delany died and now widowed for the second time, one afternoon “she noticed how a piece of colored paper matched the dropped petal of a geranium.” (Peacock, p. 1) Thus began the most remarkable period of her long life, a late flowering in every sense.

“After making that vital imaginative connection between paper and petal, she lifted … a pair of filigree-handled scissors - the kind that must have had a nose so sharp and delicate that you could almost imagine it picking up a scent. With the instrument alive in her still rather smooth-skinned hand, she began to maneuver, carefully cutting the exact geranium petal shape from the scarlet paper.

Then she snipped out another.

And another, and another, with the trance-like efficiency of repetition - commencing the most remarkable work of her life.” (Peacock, p. 1)

Remarkably she went on to complete 985 of these “mosaicks” as she termed them. Each one a complex, perfect replica of the flower, to scale and botanically accurate, some using hundreds of tiny slivers of paper to achieve a floral verisimilitude. It would have been an incredible achievement at any period in a woman’s life, even today. But to do it in the late 18th century, in her 70s, by candlelight, surely with diminishing eyesight and hand and finger agility - my mind just can’t begin to imagine how she did it.

Peacock details the tools of Delany’s craft:

“[She] used tweezers, a bodkin (an embroidery took for poking holes), perhaps a thin, flat bone folder (shaped like a tongue depressor and made for creasing paper), brushes of various kinds, mortar and pestle for grinding pigment, bowls to contain ox gall (the bile of cows which when mixed with paint made it flow more smoothly) and more bowls to contain the honey that would plasticize the pigment for her inky backgrounds, pieces of glass or board to fix her papers, pins to hang her papers to dry. It was a feast for the tactile sense; it was dirty, smelly, prodigious.” (Peacock, p. 6)

Everything about Mrs. Delany’s floral legacy is inspirational but Molly Peacock also searches for what it means about life experience, about aging, notes that “it’s no news to anyone that we make art out of the substance of our lives.” (p. 75).

Quoting Charles Bukowski, “Age is the sum of all we do." Peacock continues with…

“That’s a bit of what happens to a plant, too. It keeps adding up until it blooms, but even after blooming, after mid-life, so to speak, it keeps going, because it has to start withering. Only in drying does the real fertility begin, the seedcase forming, and only then are the seeds available to be blown apart and travel and setle. The fierce winter of dormancy is part of it all - the biennial approach to life.” (Peacock, p. 343)

Molly Peacock’s book is a thing of beauty in itself, rich with illustrations of Mrs. Delany’s floral legacy, in language rich with allusions to the subtexts of life, of living.

The incredible results of Mrs. Delany’s work can be seen today in the British Museum in London. I haven’t yet been but it is most certainly on my bucket list. Meanwhile I treasure my copy of Molly Peacock’s Paper Garden.1

Do you know that you can write your own book on beauty? Buy (and use) my book, Weather Report: A 90-day journal for reflection and well-being, with the aid of the Beaufort Wind Scale. It’s a day to a page and at the end of each day’s entry you are invited to write or draw one thing you found beautiful in your day. I promise you that it’s a transformative practice, day by day.

How beautiful - thank you for introducing me to this book and I so resonate with having books which just comfort to know they are on your shelves :)